Understanding challenging behaviour Chapter 2

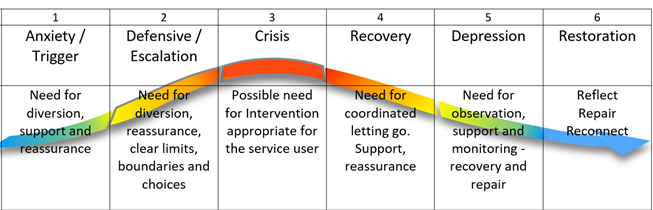

Continuing our series of blogs about challenging behaviour, Andrea and I felt that this was such an important topic, covering so much that it needed at least its own mini-series of blogs. In chapter 1 we wrote about the rage cycle and stages of a crisis. The feedback we got was really moving and it seemed to resonate with many of you out there. In it we outlined the six stages of crisis, but what next?

In this chapter I begin to unpick how, at stages 1-3 of the rage cycle, it’s really important to manage things in different ways. Andrea will pick up the baton to cover stage 4 and we will look at stages 5 + 6 in our next blog. Understanding what the cycle is and what it looks like at each point for the child or young person, as well as for yourself, will be key in this. If you can, it’s worth taking some time to watch and think about how each person responds at the different stages. To help with this we have taken these stages in turn and given some examples of what it might look like, followed by what could be done. Here is a reminder of the cycle itself.

What does anxiety look like? Stage 1

Anxiety can present in different ways but as parents hold such invaluable insights about their young person, they can be most likely to notice changes. It is often the people who know a young person best who hold the keys here. But don’t be too disheartened if this is not the case though. As the adult, we have to be in an OK place ourselves to see beyond us and what is happening with others.

Rising anxiety can be silent, loud or anything in between but key pointers can be:

- Tapping or rocking

- Hiding/pulling up collar or pulling down a hat

- Withdrawal from a situation (even from one which is familiar and usually comfortable)

- Hands over eyes/ears

- Refusing to speak or co-operate

- Being dismissive

- Going under or bending over furniture (eg table).

What can I do?

Assessing the situation and looking for key body language or signs will really help at this stage. Is it possible to identify what may be causing a rise in anxiety? If it is, point out the thing that is causing it, for instance ‘I can see that your car isn’t where you thought it was’. This gives two levels of reassurance

- that it’s OK to feel this way, we’re only human after all, and

- that this is a normal response.

Sometimes this acts as validation and will open a door in terms of finding a way out. It may not always be possible to know what is causing anxiety to rise at this point though, but just acknowledging that they are becoming upset can be powerful: ‘I can see that you’re worried’. Again, the validation will provide reassurance for the young person. You’ll need to be a bit more of a detective here to find a way out though. Whatever their level of communication, the young person will need to be heard at this point to reduce the likelihood of further escalation; there’s nothing more frustrating than not being heard. We must treat all behaviour as an attempt to communicate and it’s our job to work out what we are being told. If it’s difficult to understand the communication the young person is sharing, acknowledge that difficulty. It tells them their efforts to communicate are appreciated and you are trying.

Detective work pays off here – are there any changes in routine? Is something visually different? Could something have happened at school? Although working through these can add frustration to the situation for all involved and may lead to further escalation, hitting the nail on the head could also diffuse things in an instant. It’s worth persevering, but closely monitor the young person for signs of escalation and know that if you can’t find the source of anxiety at this point, that’s OK. But it will be crucial to identify it later to prevent re-occurrence.

Although it might be like the last natural thing to do, it’s important to stay calm. Remember what Andrea wrote about mirroring in our last blog; projecting a calm exterior can really help to de-escalate tricky situations. When I work with young people who are in distress, it really helps me to almost visualise stepping into role play at this point and I go into a ‘silent ninja’ mode. To allow the young person to have processing time I speak quietly in short sentences, with long pauses between sentences. But my mind is constantly working on questions such as ‘how did we get here?’ and ‘how do we get out of it?’ A calm stance will help with this. If you can, take a second to take a long slow breath in and feel your body relax right down to your toes on the out-breath. This will soften your stance and make you look less threatening. Be very clear with your communication – what is happening now and what will happen next? Phrasing a request as a ‘thank you’ can make a real difference too. If you say ‘Sit down, please’ this is a request and ‘no’ is a perfectly legitimate response. ‘Sit down, thank you’ implies it’s already been done and so can be a much clearer direction, potentially with less conflict. Active listening can pay dividends, listen and hear; let the young person know you are listening to them and hearing what they are saying. If they do say something inappropriate, communicate that with them. Clarity leaves less room for misunderstandings later.

In summary, as anxiety is rising in a young person:

- Assess what’s happening

- Remove frustrations (if you can)

- Stay calm

- Listen and respond in short, simple sentences

- Offer reassurance

- You could try humour or distraction to de-escalate

What does escalation look like? Stage 2

Situations escalate when the event which triggered anxiety has not been addressed or resolved. A young person may demonstrate some or any of the following as the amount of energy going into their response increases:

- Start to become destructive or pick up ‘weapons’

- Display tension by moving around or starting to hit out

- Increased volume, pitch or speed when speaking

- Change in degree of eye contact (more intense, significantly reduced or none)

- Verbal challenges eg ‘no’ or ‘you can’t make me’

What can I do?

At this point, the young person displaying the challenging behaviour may still be able to reason and to listen and understand what you are saying. But the likelihood of this decreases as the anxiety or severity of behaviour increases. With that in mind it will be important for you to use less language so that they have a better chance of processing what you are saying; shorten phrases and use minimal words. By all means outline what behaviours are expected at this point, but also offer a life-line if the young person isn’t able to or doesn’t comply. Potentially, the young person could be digging themselves into a hole they can’t get out of. If you back yourself into a corner by shouting/being aggressive, how do you get out of it? You need to give them an alternative which offers a dignified way out for you all. We mentioned this ‘ladder’ in our last blog; by offering it before a crisis really kicks in, there may be a chance the crisis can be averted.

As a situation escalates, you will need to constantly risk assess the area and make it as safe as possible. Is there room for you to step back to allow the young person space to breathe and then respond? Offer alternatives or distractions – ‘shall we go and…?’. Sometimes an outstretched hand (to be taken) can help here as this offers a visual way out too but you will need to make sure the young person has space to move to take your hand.

Distractions can work either way at this point. An audience might be a distraction you don’t want – if that’s the case ask people to move away. However, a distraction of offering a job or task to the young person which they like might work too. Without selling your soul, being a ‘bigger’ person and offering a favoured way out could stop the situation reaching crisis point. It’s hard, really hard. You feel like you’re giving in, like the young person is ‘winning’. But how can someone be ‘winning’ when they’ve shared some of the least loveable aspects of their personality with you? A dignified get-out can reduce the likelihood of a crisis; you can resolve any issues you may have with the carrot afterwards. From my experience, coming to terms with my issues around what I sometimes saw as rewards could take different amounts of time. Sometimes I got it straight away and it was OK, in one situation I was still pondering on it three months later. In all cases though, the situation was de-escalated, either from this stage or the next.

In summary, as the situation escalates:

- Assess what’s happening

- Continue with previous responses (unless they’re clearly not working)

- Stay calm

- Make the environment as safe as possible

- Remove any audience

- Offer clear choices (including a dignified way out)

- Use distraction to bring in a positive focus

- Get help if you need it

What can I do at crisis point? Stage 3

At crisis point, the young person is likely to be hurting themselves or someone else, causing damage or even committing a criminal offence. Danger could also be a factor here; is the young person fiddling with electrical fittings or looking like they might break a window? If they are, they need to be supported to be safe. Safety is a key concern, for everyone involved. Could the area be made safer by moving furniture etc? Would the young person be safer in a different place and so needs escorting there? One thing that is likely is that this stage will be ugly. Even with best intentions, a physical support could become messy and thoughts about personal presentation are rarely a priority at this point. Young people and the people supporting them could perhaps sustain an injury because of the intense energy being discharged. This happens. If it happens to you, be honest about it. A cover-up, even to ourselves, is likely to fester and come back as something much bigger. Facing this is a really important part of the recovery process too. It is also likely to be a relationship changer. When rage takes over in a crisis, the actions of a young person are very rarely, if ever, personal. However, the effects can be devastating. It is really important to acknowledge how hard it was but then make a committed effort to restore the relationship.

In summary, as a situation reaches crisis point:

- Keep safety for all as a paramount concern

- Remove things if you can (such as furniture or objects), to make the environment safer

- Keep interactions supportive

- The young person may need some physical support to remain safe

How can we recover from this? Stage 4

Recovery is the point where things begin to appear to calm down, but it’s important to remember that this is a really critical time and the wrong approach here can quickly re-ignite stress and anxiety. On the other hand finding and offering the best calming strategies at this point is vital. Take some time to observe the young person in their calmest, most relaxed moments. What are they doing? What is it that really relaxes them? This is not likely to be something that they find incredibly exciting or might obsess over, such as devices, in fact it’s best to avoid those things. Remember that doing something that relaxes you can be very different from doing something that you enjoy. For some people being in dark or enclosed spaces is calming, for others it’s listening to or playing music, maybe colouring or running soft fabrics across their skin. They might not even realise that they have a ‘thing’. For me its fiddling with my hair. I didn’t even realise this until recently, but it’s something I’ve always done and it just really chills me out. Everybody has something. It really is worth thinking about this at times when there are no stressors and when everyone is really calm. If the young person is able to, it’s worth working them out together and making a list of things that they can use to relax. Make up a box of things that can be used during the recovery stage if the relaxing activity lends itself to this.

Once this stage in the rage cycle has been reached, calmly remind the young person that they can use these strategies to help themselves relax. For instance, you can do this by simply showing them the things that they use, pointing to the list that they have made or by showing them symbols that they associate with those activities. Then give them space and time to relax. Don’t talk too them much at this point, instead offer calm and relaxed quiet. Avoid lots of conversation as this might trigger a relapse to a heightened anxiety stage. You might feel that you have to talk with them about the events that led up to the crisis point, but trust that this can happen at a later time.

In summary, as a situation reaches recovery:

- Pinpoint activities that help to calm and relax

- As far as possible involve the young person in working out what helps them

- Offer calming activities when the recovery stage has been reached (it might also help to offer these activities during stage 1 and 2 as a de-escalation strategy)

- Keep the atmosphere as calm as possible

- Give space and time for recovery to occur

- Trust that there will be a time to talk about everything at a different point

In this week’s blog we have broadly outlined some strategies that are appropriate to implement at different stages, and we hope they give you somewhere to start when thinking about your own personal circumstances. We also know that every situation is different and if you have any questions please do ask us. If you think that we can help you please contact us via our email or social media; you can find all the links to the left of this page.

Let us know what you think of this week’s blog via email or comment on our links on the Together social media pages. Check in with us again next Friday when we will be blogging about the last two stages of the rage cycle: Depression and Restoration. Supporting people appropriately at these stages is perhaps the most vital and sometimes most overlooked part of the process. Take care everyone!