Understanding challenging behaviour Chapter 1

When a child exhibits challenging behaviour in the home it can be incredibly hard to deal with, especially if those challenges result in violence towards family members or self-harming behaviours. Of course it’s hard to deal with challenging behaviour in school, balancing the needs of the class with the needs of the individual, making sure that you deliver the curriculum, prioritise where staff should focus their attention, keep everyone focused, considering if everyone is safe and if there’s a need for any physical intervention, (always the last resort). There have often been times when I’ve been totally exhausted at the end of the day, occasions when I have wondered if I had what it takes to work with a particular child or class. But I know for a fact that working with an anxious, possibly violent, child in school is not a patch on dealing with these issues at home.

When it’s your own child that is melting down in front of you, and possibly all over you, there is vastly more going on and so much more at stake.

Trust, harmony and understanding can be replaced with distrust, hostility, and enmity. All of these negative feelings, if left without resolution, over time can erode feelings of love. And when you begin to question your love for your child, your child’s love for you, or your child questions your love for them, it can be devastating. It’s certainly devastating for the child, whether they realise it or not. The net result is a spiral downwards where the expectation is that there will always be a poor outcome. This feeling becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy so that there always is a poor outcome. A breakdown of relationships in school, where the depth of love is not as great and everyone can walk away at the end of the day, can not compare to a breakdown in relationships at home.

My husband loves the phrase ‘the definition of stupidity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results’. A little harsh perhaps? He says it to me often. I’m not entirely sure why… But he really does have a point and particularly when it comes to trying to change challenging behaviour. If we, as parents, continue to respond to challenging behaviour in a way that has never yet been successful how can we expect a more positive outcome?

From the perspective of the child or young person, if they continue to respond in an aggressive way and it has never resulted in a positive outcome for them how can they expect that it will benefit them at all in the future. So why don’t they try something different? The problem is that most aggressively challenging behaviour occurs at a point when they no longer have the ability to think through the ramifications logically so the chances that they will try to change their behaviour are slim. Clearly something has to change.

In fact a number of things have to change. And the key to it all is the understanding of the adults around the child or young person.

When I first learned of ‘mirroring’ it had a profound effect on the way I began to deal with people presenting with challenging behaviours. Simply put, ‘mirroring’ is when we unconsciously copy the behaviour, speech pattern and emotions of those around us. It is thought to support social interaction by helping us to feel more at ease with each other. However, it can also work in the opposite way. Have you ever seen two people in a road rage incident for instance? Each person meeting the other with anger which just continues to erupt ever more impressively? So if mirroring aggression works to incite more aggression, it should be possible to begin to calm someone by making sure that your body language and tone of voice is as calm as possible. Projecting a calm demeanour can begin to reduce elevated behaviour. But yes, this can be easier said than done, especially when you don’t actually feel calm. Projecting a calm exterior in order to de-escalate is really important, but it is just one strategy in a much larger toolbox. After all, if we project a calm exterior to an aggressive person, how do they learn how deeply inappropriate aggression is?

In our first blog on challenging behaviour we are focusing specifically on the sequence that people go through when they are in a state of distress, often referred to as ‘the rage cycle’. It’s incredibly important that we all understand this sequence in order to be able to offer the right support at the right time. In Deb’s work as a Team Teach Tutor she helps people to think about the rage cycle in order to understand what can lead to meltdowns and how to develop support strategies. She outlines below the model used within the Team Teach Framework, which is a holistic behaviour approach (other approaches are available).

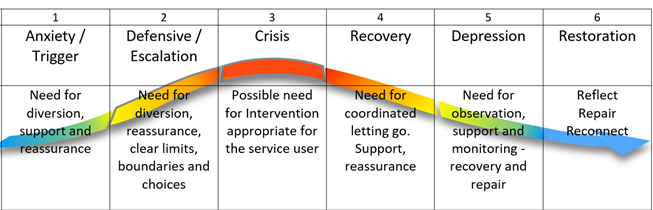

There are different ways to visually portray the rage cycle or stages of a crisis. One that we have worked with is called the six stages of a crisis. It is based on the five stages mapped out by Kaplan and Wheeler (1980) but has been further developed. The visual below shows the six stages, simplified from a version used by Team Teach:

The six stages identified include:

Anxiety/trigger: something sparks a behaviour. Even though a trigger may have been something from 1 minute ago, 1 day ago or even 1 week ago, it is more than likely that it exists. Working to find this out pays dividends in understanding how a crisis might be avoided in the future.

Escalation: with the trigger and behaviour not understood or diffused, escalation is likely. This stage is key as there is still a chance that at this point, the young person displaying the challenging behaviour may still be able to reason. But the likelihood of this decreases as the anxiety or severity of behaviour increases.

Crisis: this may look different at different times. It can range from violence, to extreme withdrawal but one thing that is very likely at this stage is that the young person will need support. For them, it may be as though they have dug themselves into a big hole and can’t get out of it on their own; they will need someone to throw them a ladder. It is extremely unlikely that a young person will be able to reason at this point, as rage will have taken over. The key focus here is to make sure that everyone involved is as safe as they can be and that the young person is supported with strategies to help them de-escalate. This will look different depending on the behaviour and the young person. Sometimes positive touch will help, sometimes it won’t. Knowing the young person and what they may respond to is invaluable at this stage.

Recovery: at this stage, it’s about reducing the intervention that was put in at the crisis point. It’s really key to watch for signs of calming and to respond to them.

Depression: this is where the reality of the situation can kick in; no-one wants to feel out of control but at this point, it may register that they have been. A young person may feel disappointment, shame or a whole host of other negative feelings. Again knowing the young person is key here. They may need close support at this point or they may need space.

Restoration: this can never be valued enough. Supporting a young person in crisis can be a relationship changer for everyone involved. There is a small chance it could improve the relationship; ‘I went into crisis, needed someone and you were there’. It could also damage the relationship as actions and their consequences may shake the trust in a relationship. When rage takes over in a crisis, the actions of a young person are very rarely, if ever, personal. However, the effects can be devastating. It is really important to acknowledge how hard it was but then make a committed effort to restore the relationship. There are different ways to do this (and it can only be done when everyone involved is ready) but key points to consider include:

- How did you feel?

- What could you do next time you feel that like that?

-

What were the good choices/bad choices

- What can be done to make things better?

There are other important things to think about with this cycle. The graphic is a very linear picture, the reality is often very different. One stage may last much longer than another, you may hardly notice a stage or it could be skipped entirely.

- There is no timescale.

- The recovery may take 30 minutes, 3 hours or 3 months.

- All responses, although they can challenge, are OK.

- There is also no ‘calm’ line at the beginning, we don’t always have to be on an ‘up’ or a ‘down’, we might be just OK.

- There is no guarantee that this will be an ‘in’ and ‘out’ process and that stages 1-6 will flow. A young person may exhibit stages 2 – 4 and then go back to stage 2.

- Don’t assume it’s over until it is!

- Everyone involved in this cycle is equally important. Yes, the young person will need support but so will those supporting them. No-one signs up to enter into a crisis with a young person, who can help you with how it affects you?

- It is a perfectly normal human response to feel knocked, bruised, low in confidence, unloved or depressed afterwards. Please get the support you need too.

If you feel that it would be useful to develop your understanding of this cycle, please feel free to contact us for support by email or through our Facebook page.

Challenging behaviour is a huge topic and there are never any easy fixes. Deb and I have only just scratched the surface here. In our future blogs we will look at the need to feel some control, strategies that can be used and the importance of understanding emotions. We hope that this chapter in our series on challenging behaviour has given you some food for thought and helps you to begin to make some sense of what might be happening. Do check out our upcoming blogs in the coming weeks and let us know your thoughts on this chapter via our Facebook page or contact us via email.